According to the UN, at least one third of the

global urban population suffers from inadequate living conditions. Lack of

access to basic services (drinking water and/or sanitation, not to mention

energy, waste recollection, and transportation), low structural quality of

shelters, overcrowding, dangerous locations, and insecure tenure are the main

characteristics normally included in the definitions of so-called informal settlements.

Recognized as a global phenomenon, no

country can claim to be free of informal settlements, although the numbers of

people suffering can vary largely depending on the region: these problems now

affect up to 60 percent of the world’s population—or even more—in some

Sub-Saharan African and Southeast Asian cities, and the number of people

affected in these locations is expected to double over the next two decades.

High percentages are also seen in several Arab countries, and at least 25

percent of urbanites in Latin America live in informal settlements. Precarious

housing and living conditions and growing homelessness can also be found in

Europe, North America, Australia, and New Zealand, affecting, on average, one

in 10 people.

Squatter settlements,favelas, shacks,villas

miseria,bidonvilles, slums, and many other

names are typically used to refer to such impoverished neighborhoods. In

general terms, all of these names highlight their negative characteristics and

clearly imply pejorative connotations. By cruel extension, the words used to

describe the physical conditions of the settlements also tend to apply to their

inhabitants. Despite what normative frameworks might say about all persons

being equal before the law and the state, inhabitants of informal settlements

are generally treated as second-class citizens.

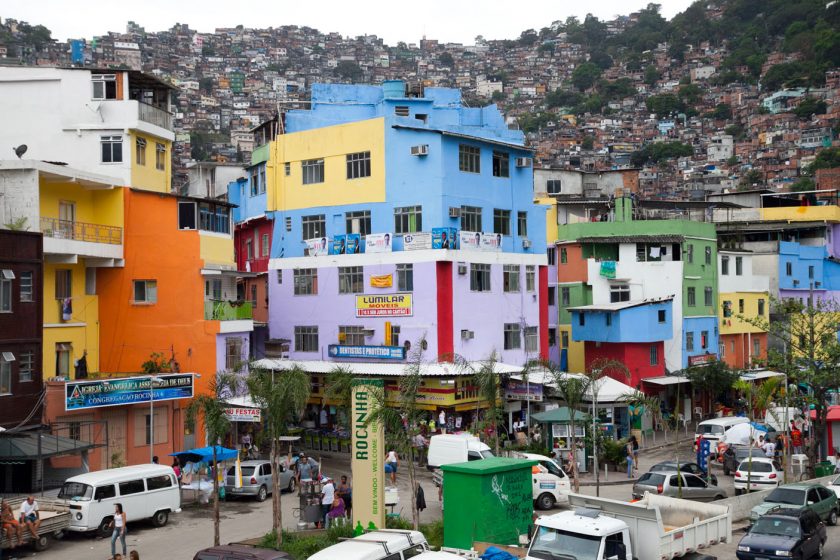

Rocinha (“little farm”, due to its agricultural

vocation until the mid 20th century), located in the rich southern zone of Rio

de Janeiro, is considered one of the most populous favelas in Brazil. Most of

its 70,000 inhabitants live in houses made from concrete and brick and have

access to basic sanitation, plumbing, and electricity. The neighborhood has a

vibrant local economy. Source: Alamy.com

Colorful

houses at the base of the Rocinha Favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Image shot

2010. Source: Alamy.com

In academic and government documents, “informal settlements” is the

label typically applied to these areas. That those communities are not in

compliance with building norms and property and urban planning regulations is

often given as the main reason for qualifying them as “informal”. Also defined

as “irregular”, they can easily be called “illegal”, and their inhabitants

subsequently criminalized, displaced, and persecuted. From India to South Africa

to Ecuador, legal and administrative changes have been made in recent years to

give special/ad hoc inspection and demolition powers to local, provincial, and

national governments to deal with these neighborhoods and, in theory, to

prevent them from growing (in many cases, environmental laws and regulations or

urban projects are used as excuses for destroying these settlements). As was

recently recognized, the UN’s Millennium Development Goal 7-Target 11

commitment to reducing the population living in slums by 2020 was tragically

translated in several countries as the pressure to destroy people´s self-built

housing and even to incarcerate the leaders of social movements (for a critical

analysis of the “cities without slums” initiative and why language matters, see

Gilbert, 2007). In Zimbabwe alone, the UN reports that as many as 700,000

people were affected by terrifying slum “clearance” operations in 2005, which

took the revealing name of “Remove the filth”!

At the same time, these areas are frequently presented as empty, colored

grey or green on maps. As we all know, not having an official address (street

name and house number) is a huge obstacle to being able to fulfill other needs

and rights: applying for a job, sending one’s kids to school, being admitted

into health systems. Invisibility and stigmatization of citizens living in

particular neighborhoods go hand in hand and make poverty, exclusion, and

discrimination self-perpetuating. Social exclusion often means spatial

segregation, and vice versa.

Following a tradition most probably started before the mid-19th century

in some English cities undergoing industrialization processes and migration

from the countryside, our contemporary media still often depict the inhabitants

of informal settlements as the troublemakers, the thieves, the lazy. It is hard

to find positive stories about their daily struggles for better life

conditions, rights, and dignity.

It is clear that we urgently need a better approach to naming and

framing such areas broadly called “informal settlements”—one that is respectful

and sensitive to the people who live there and that could better promote the

transformations that our cities and our societies need.

Questioning the formal/informal dichotomy

The “informal settlements” label does not reflect, nor does it take into

account, the many variations that these popular settlements present in

different parts of the world. Using “slums” or “informal settlements” to

describe Kibera in Nairobi or Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro does not seem

appropriate when, just by looking at some pictures, anyone can tell that they

present many differences in terms of quality and durability of the housing

materials and access to basic services and infrastructure, to mention some of

the more visible contrasts. We can then look to statistics and realize that while

the cariocas of Rio have private bathrooms in every housing unit, their fellows

on the other side of the ocean only have 1,000 public toilets for 180,000

people. Not only that: as a consequence of massive investments during the

recent years in neighborhood improvement programs, a Rio favela house

with a view of one of the many wonderful bossa-nova bays might now reach US$ 250,000 in value—and rumors that Hollywood stars are

buying them are widespread.

Likewise, the classification of all such areas as “informal settlements”

does not indicate the relevance of the places in their cities that they occupy

or the spatial segregation they usually suffer from; the lack of access to

affordable and public transportation, places of employment, schools, hospitals,

and other basic facilities; the lack or limited access to financial resources

such as credits, subsidies, etc.; or the lack of technical assistance and/or

adequate materials to consolidate housing and neighborhoods buildings and

infrastructure, just to mention a few.

Originated as a settlement at the outskirts of

Nairobi for Nubian soldiers returning from service with the British colonial

army more than a century ago, Kibera (“forest”) is known as the largest slum in

Africa. Before Kenya´s independence, the law strictly segregated and

discriminated non-Europeans groups from political, economic and social rights.

Photo: Mathare Valley. Source: Alamy.com

Kibera,

Nairobi, Kenya. Photo: Mathare Valley. Source: Alamy.com

The difficulties of defining a phenomenon so varied and dynamic as

“informal settlements” are often invoked to justify the continuing use of the

catchall term and the predominant focus on what they do not have (Connolly,

2007). But academics in several regions have been discussing the

formal/informal false dichotomy as a kind of “discursive differentiation” that

shapes and enacts knowledge and power relations on the territories. Many of

them argue that binary classifications are clearly insufficient to reflect the

complexity of settlement processes that we face in reality; such

classifications simultaneously hide authorities’ responsibilities in producing

informality (Roy, 2009; Yiftachel, 2009; Wigle, 2013).

By defining what is formal and regular, and changing those definitions

over time, according to political interests, involved governments maintain

these settlements in a “grey” zone of non-definition and permanent negotiation

that makes their inhabitants more vulnerable to clientelistic practices

(understood as exchanges of goods and services for political support), which

are particularly intense during electoral periods. The above authors go so far

as to denounce that “the use of such binary categories also entails an

uncritical view of regular settlement areas” (Wigle). On a related note, the

irregularities in accessing urban services and/or violations of land-use and

other planning norms in rich neighborhoods are not punished and, in many cases,

are even presented and considered as positive ´investments´ that benefit the

community as a whole. Based on such considerations, formal/informal,

regular/irregular are ever-changing and mutually-defined categories and not

fixed, contrasting entities.

In more general terms, these classifications do not allow us to analyze

the profound, structural causes that explain the creation of precarious and

inadequate settlements: expulsion of rural, campesino,and

indigenous people due to the lack of government support for small and

medium-sized agriculture; lack of mechanisms to control land grabbing and

speculation; evictions and displacements due to multifactorial crises, social

conflicts over land, resources, and natural or manmade disasters; urban renewal

and “development” projects; lack of facilities and services; lack of affordable

land and housing policies; social vulnerability and low-paid, unprotected jobs;

lack of opportunities for youth; discrimination and marginalization.

Without considering the causes, how would we be able to reverse those

tendencies and find the needed solutions?

The city produced by the people: the urgent need to understand it and

support it

Academics aren’t the only ones who have being questioning this negative

and limited approach. For more than 50 years, civil society organizations,

engaged professionals, and activists have being analyzing and supporting these

processes from a different, but also critical, point of view.

This movement, described as Social Production of Habitat, intends to

highlight the positive and transformative characteristics of so-called

“informal settlements”, which involve people-driven and people-centered

processes to produce and manage housing, services, and community infrastructure.

In other words, processes of practical problem solving for achieving human

dignity and a better quality of life.

“Social Production of Habitat” is a phrase intended to describe people

producing their own habitat: dwellings, villages, neighborhoods, and even large

parts of cities. They may be found in rural and urban settings, ranging from

spontaneous individual/familial self-constructions, to collective productions

that imply high levels of organization, broad participation, and agency for

negotiation and advocacy with public and private institutions—although, in

general, they are implemented with very little or no support and often despite

a myriad of economic and institutional obstacles (Ortiz and Zárate, 2002).

In recent decades, Habitat International Coalition, or HIC (full disclosure: I am

currently serving as President of HIC), and other international networks have

been documenting some of these collective initiatives in various parts of the

world. Different kinds of organized social groups (social movements,

cooperatives, tenants’ federations, women’s organizations, etc.) are driving

innovative experiences that cover a broad range of activities: from accessing

land and building housing and basic infrastructure, to the responsible

management of the commons (water, forests and green areas, public spaces and

community infrastructure); from gender equality and human rights promotion and

defense, to food production and preservation of cultural identity.

The underlying, essential factor is that these initiatives and projects

consider the production of housing and human habitat as a social process, not

just as a material product. The collective effort to build and produce a place

to live is not a mere object for exchange. It is a combination of different

types of knowledge, expertise, materials, and other in-kind contributions from

different actors and institutions, and not something that one can just buy (or

not!). It is a social relation and not a mere commodity.

Instead of “informal settlements”, we prefer to understand and describe

them as practices and social struggles that not only build houses and

neighborhoods strictly on a physical level; at the same time, and perhaps even

more importantly, they also build active and responsible citizenships against

marginalization and social and urban segregation, advancing direct democratic

exercise and improving individual and community livelihoods, participants’

self-esteem, and social coexistence (Ortiz and Zárate, 2004). In fewer words:

the city produced by the people.

When organized, recognized, and supported (with the appropriate legal,

administrative, financial, and technical mechanisms), these processes have a

relevant positive impact both at the micro- and macroeconomic levels. Given

that official statistics usually do not measure these people´s and communities´

efforts, HIC members have promoted research and dissemination projects with

different academic institutions. The findings show that

in places such as Brazil or Mexico, the Social Production of Habitat represents

a constant contribution of around 1 percent of GDP (even in times of serious

economic crisis, when public and private actors reduce their investments

considerably); at the same time, they explain the multiple ways in which such

social initiatives activate and strengthen several circuits of the local

economy, at small and medium scales (construction materials and labour,

professional services, etc.) (Torres, 2006).

At the same time, and thanks to their innovative proposals and concrete

results, individuals and organizations engaging in the Social Production of

Habitat have influenced the reorientation of housing and urban development

policies and contributed to generating changes in legal, financial, and

administrative instruments relevant to social housing, self-managed processes,

tenure security, attention to low-income sectors, and environmental

improvement, among other issues.

Social Production of Habitat as a fulfillment of human

rights

Social Production of Habitat movements and projects fill the gaps left

from the state’s failure to respect, protect, and fulfill human rights,

particularly the human right to adequate housing and other related rights:

property, water and sanitation, participation, non-discrimination, and

self-determination, just to mention a few. Moreover, the right to produce and

manage our habitat is one of the strategic components of the right to the city.

That being said, it is fundamental to highlight that people’s agency to

improve habitat does not absolve the state of its obligations to citizens and

residents (Schechla, 2004). According to the international commitments that

they have signed, governments—both at national and subnational levels,

including regional, provincial, and local authorities—are obligated to refrain

from forced evictions, confiscation and repression of human rights defenders,

discrimination, corruption, withholding services, and other such violations.

State institutions and officials should abstain from actions that would

obstruct the social production of housing process, in particular through

housing destruction and displacements. As established in standard-setting instruments, when resettlement is the only

available option (i.e. due to a disaster-prone location or similar issue), the

participation of the affected community and families is mandatory in agreeing

the details of the process and negotiating appropriate resettlements (including

providing shelter in a nearby location so as not to affect people´s livelihoods

and social networks), as well as just remuneration and compensation measures.

At the level of protection, state obligations in the social production

of housing process involve the provision of safeguards and assurances of

freedom from unnecessary and disproportionate use of force, public-service fee

increases, monopolistic control of building materials, and other impediments to

the people’s process. The state also bears the obligation to prosecute

violators and ensure effective relief and remedy for victims. Measures that

prevent, deny, or repress the inhabitants’ rights to association,

participation, and free expression in the physical development process would

also violate the obligation to respect the human right to adequate housing.

At the fulfillment level, the state possesses unique capacities to

ensure, recognize, and support people´s efforts and community-led efforts.

Enabling social production of habitat policies, programs, institutions, and

budgets is fundamental, including those that can guarantee access to:

- land in

good locations - security

of tenure, prioritizing women´s needs and rights - services

and infrastructure - adequate

financial resources and schemes (credits, subsidies, and savings; recognizing

people’s in-kind contributions) - professional

technical assistance - information,

materials, and technology - cross-sectorial

training

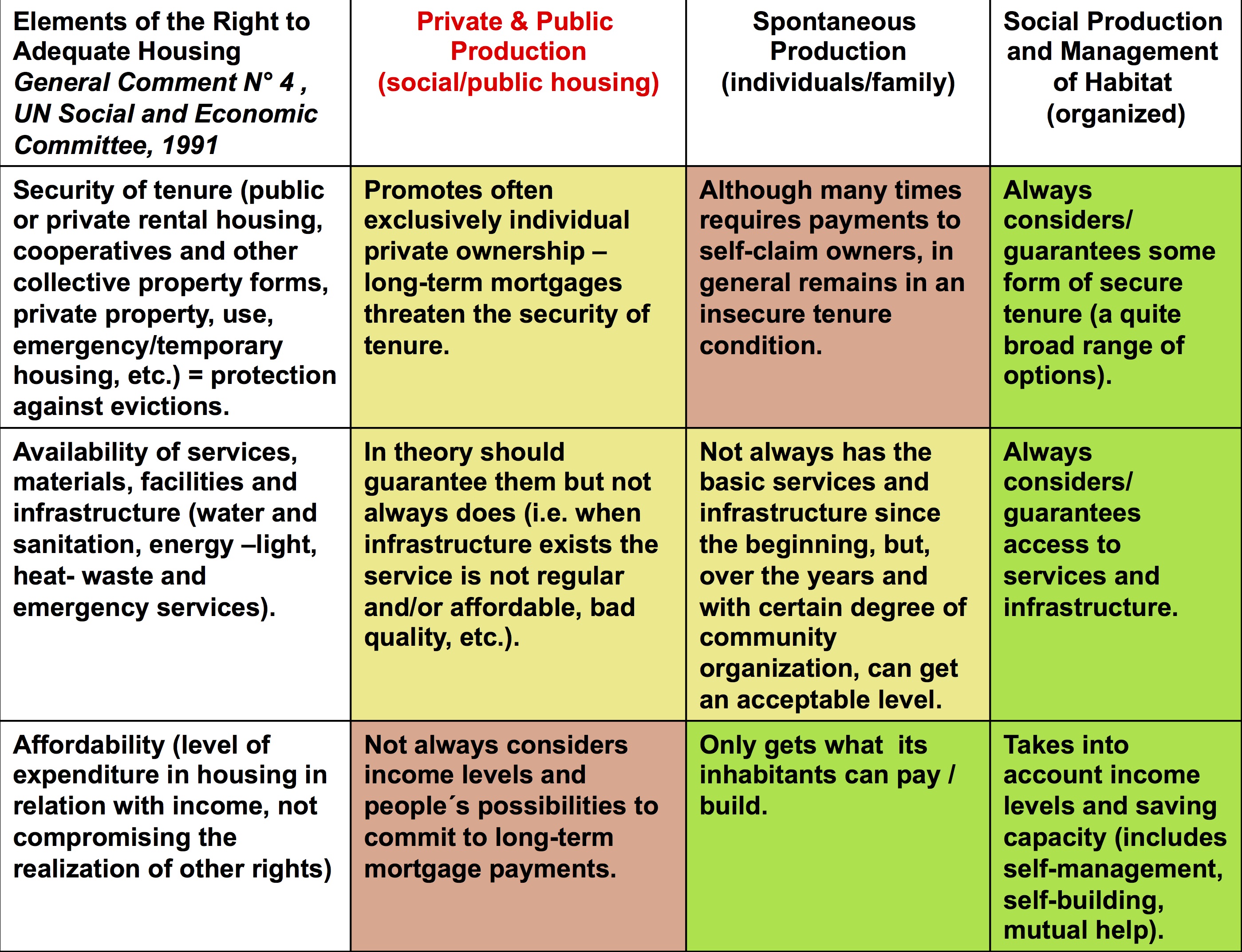

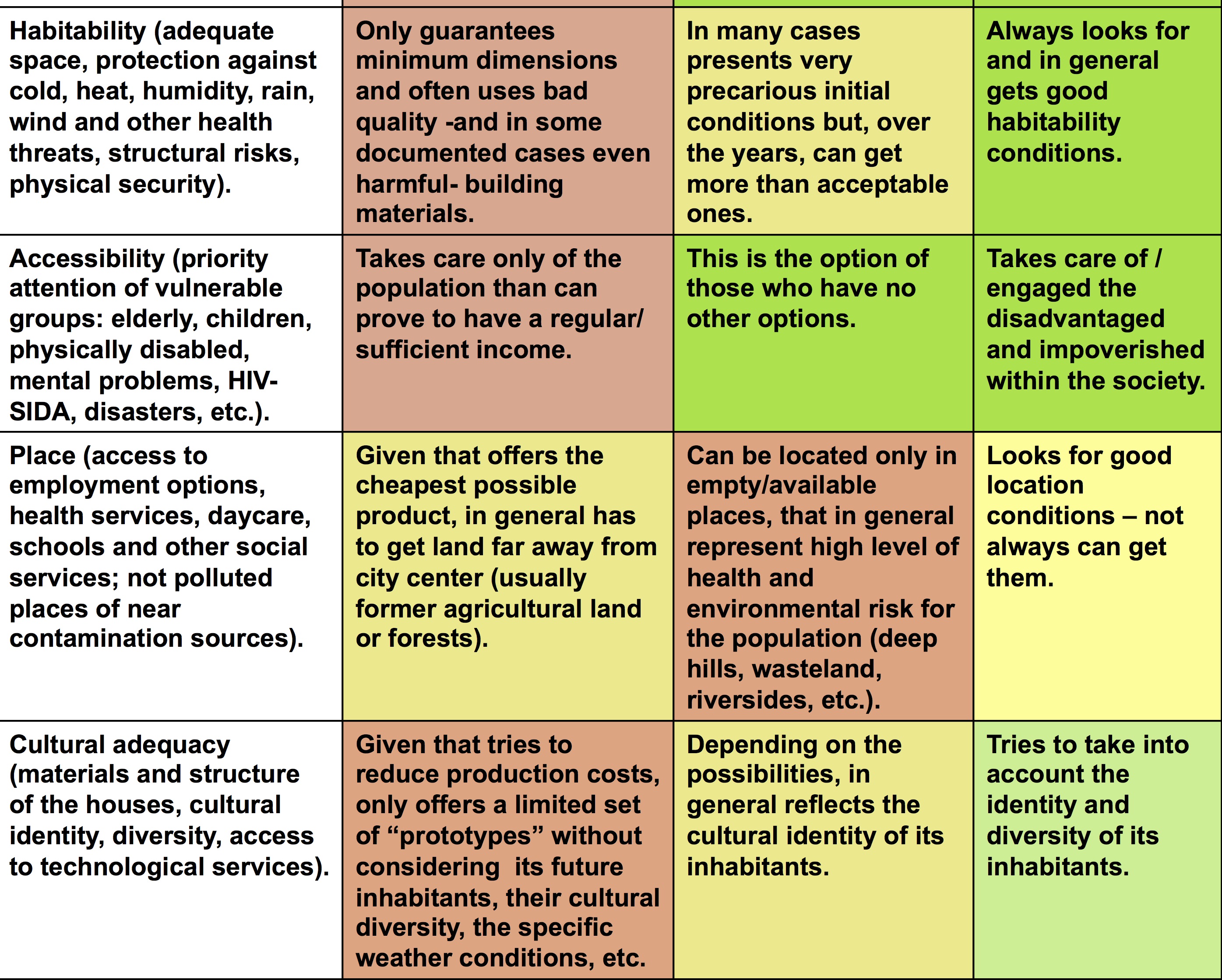

Comparing different forms of producing housing and

neighborhoods in face of obstacles to the right to adequate housing.Red: weak/no

compliance; Yellow: mid compliance; Green:high

compilance

A new

urban agenda 2016-2036: a paradigm shift?

The third UN Conference on

Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (known as Habitat III) will take place in Ecuador in October 2016. For

almost two years now, multiple actors and institutions, including national and

local governments, social movements and civil society networks, youth and

women’s organizations, academics, professionals, journalists, and the UN and

other international agencies have being participating in debates, declarations,

and other documents that will serve as inputs for what should be the

Conference’s main outcome: a “New Urban Agenda”.

An initial set of written

materials, the so-called Issue Papers, was produced during the first half of 2015 and

dealt with 22 relevant themes. One of those themes was informal settlements, which tried to provide definitions of

pertinent key words (without mentioning any critics or limitations), some

updated global figures and facts, as well as relevant recommendations. Those

“key drivers for action” included eight topics: Recognition of the informal

settlement and slum challenge and the mainstreaming of human rights; Government

leadership; Systemic and city-wide/‘at scale’ approaches; Integration of people

and systems; Housing at the centre; Appropriate long term financial investment

and inclusive financing options; Developing participatory, robust, standardized

and computerized data collection processes; and Creating learning platforms.

Although they might not be sufficient, each of these eight topics is

fundamental, and the group of topics certainly reflects many of the concerns

and proposals for which civil society and social organizations have been

advocating.

However, it seems that those

important analyses and recommendations did not make their way into the second

round of official documents, the Policy Papers (February

2016). None of those 10 papers dealt exclusively with informal settlements, and

their contents do not seem to take into consideration the concepts or key

drivers discussed in the previous Issue Papers. It is true that a few weeks

ago, an official thematic preparatory meeting on this particular topic was held

in Pretoria, from which arose clear and strong recommendations on relevant

elements such as land policy (balanced territorial development and urban

planning), protection against evictions, participatory and in situ

slum-upgrading programs, among others; but, again, no critical review on the

concept or alternative definitions were considered in its declaration.

At the same time, the social

production of habitat is mentioned several times in different documents, but

only in a very limited and superficial manner, despite the prolific and solid

contents and formal commitments that the predecessor Habitat Agenda (Istanbul, 1996) managed to include.

Today, as yesterday, our networks will continue to push so that a more accurate

definition, analysis, and policy recommendations are considered in the new

agenda (see Mexico City Declaration on Financing Urban Development, March

2016). Bringing the communities´ voices to the debates and showing the

achievements and challenges that they face should be one of our main tasks.

Changing the words means

changing the concepts; changing the concepts means changing the way we

understand (or not) complex phenomena and are able (or not) to transform them

in a positive way.

Neither informal nor irregular,

these are, above all, human settlements. Or even better: they

are the city produced by the people: the people who claim their rights to live,

build, and transform the city.

Lorena Zárate

Mexico City

References

Connolly, P. (2007) Urbanizaciones irregulares como forma

dominante de ciudad [Irregular urbanization as predominant city form]. Unpublished

paper presented at the Second National Land Use Congress, Chihuahua, Mexico,

17–19 October.

Gilbert,

A. (2007) The Return of the Slum: Does Language Matter?International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 31.4: 697-713.

Ortiz, E. y L. Zárate (2002) Vivitos y coleando. 40 años trabajando

por el hábitat popular en América Latina [Alive and kicking. 40 years

working for people´s habitat in Latin America]. Universidad Autónoma

Metropolitana y HIC-AL, Mexico City.

Ortiz, E. y L. Zárate (2004) De la marginación a la ciudadanía. 38

casos de producción y gestión social del hábitat [From Marginality to Citizenship. 38

cases of social production and management of habitat]. Forum Universal de las

Culturas, HIC y HIC-AL, Barcelona.

Roy, A.

(2009) Strangely familiar: planning and the worlds of insurgence and

informality. Planning

Theory8.1: 7–11.

Schechla,

Joseph (2004) Anatomies

of a Social Movement. Social Production of Habitat in the Middle East/North

Africa (Part I). Housing

and Land Rights Network-Habitat International Coalition, Cairo.

Torres, Rino (2006) La

producción social de la vivienda en México. Su importancia nacional y su

impacto en la economía de los hogares pobres [The social production of housing in

Mexico. National relevance and impacts in the economy of low income

households]. HIC-AL, Mexico City.

Yiftachel,

O. (2009) Theoretical notes on ‘gray cities’: the coming of urban apartheid? Planning Theory 8.1: 88–100.

Wigle,

Jill (2013) The ‘Graying’ of ‘Green’ Zones: Spatial Governance and Irregular

Settlement in Xochimilco, Mexico City. International Journal of Urban and

Regional Research38.2:

573-589.