Diplomatic negotiations can be a high-stakes game

Diplomatic negotiations can be a high-stakes game

of poker, with countries attempting to play their cards without giving away

their hands. But for anyone following the preparation of the New Urban Agenda, the United Nations’ 20-year

urbanization strategy, there are already clues as to the potential battle lines

in the global debate over human settlements.

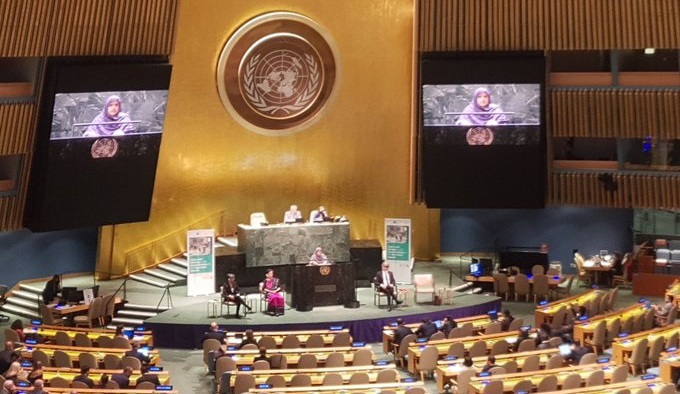

The New Urban Agenda will be adopted in October at

the U. N.Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban

Development, or Habitat III, which will take place in Quito,

Ecuador. Ahead of that summit, the U. N.has

asked 200 experts in housing, urban planning, architecture, public policy and

finance to tackle the big issues at the foundation of today’s urbanization

debate.

On New Year’s Eve, these 10 “policy units”, as they are called,

each delivered a framework of ideas that together constitute a likely rough

outline for the New Urban Agenda, the first draft of which is expected in early

May. Meanwhile, the policy units are currently working on final drafts of these

papers, which are expected imminently.

[See: Key drafts of Habitat III policy papers open for public comment]

Last month, 16 countries submitted comments on

these frameworks, which were published on the Habitat III website. Many of the comments were technical,

with diplomats having to remind the authors — most of whom come from outside

the U. N.system — that the New Urban Agenda will not

exist in a vacuum. By custom, then, it must refer to its predecessor documents,

a laundry list of international agreements over the past two decades on topics

such as sustainable development, climate change, disaster risk reduction and

road safety.

But other comments — which range from nitpicky

requests for the insertion or deletion of a word to wholesale ideological

disagreements — foreshadow tensions that could bubble up during the

negotiations over the New Urban Agenda, which will take place this spring and

summer before the final showdown in Quito.

With 193U. N.member

states, the published comments from these 16 also offer a sneak peak of which

countries are most engaged in the outcome of the conference. Since countries,

after all, will be the ones to decide on the final text of the New Urban

Agenda, knowing who is paying attention and what they care about will be

important strategically for the constellation of groups lobbying for certain

issues to make their way into the document.

[See: Stakeholders concerned over access to Habitat III negotiations]

Rights or wrong

One of the clearest early divides has come up

around a global “right to the city”. A group called the Global Platform for Right to the City (GPR2C) hopes that this idea constitutes a core part of the New

Urban Agenda, and many of them prepared a policy framework with precisely that

theme. (GPR2C is funded in part by the Ford Foundation, as is Citiscope.)

Called “Rights to the City and Cities for All”, the

outline pointedly calls for this idea to be the centre piece of the new

strategy.

[See: A needed cornerstone: The Right to the City]

There is no universally agreed definition of the

right to the city. The concept generally refers to an inclusionary vision of

cities that provide adequate shelter, employment and public services to all

residents, including traditionally marginalized groups such as women, youths,

minorities, immigrants and the homeless.

The idea is popular among leftist critics who see

contemporary cities as beholden to financial interests and besot by

privatization, resulting in places of increasing inequality where real-estate

speculation trumps the “social” function of land. For example, a privately

owned lot intentionally left vacant to appreciate in value would be better

served by affordable housing or a community centre, advocates of a right to the

city would say, and public policies should compel the more equitable outcome.

The 10 experts of the policy unit focusing on these issues appear

to agree with much of this. As their draft policy paper states, “Contrary to the

current urban model, [the right to the city] aims to build cities for people,

not for profit.” Subsequently, these experts argue that Habitat III must

be based on a human-rights framework, echoing the 1996 Habitat Agenda, which they note makes 26

mentions of human rights.

[See: Fractured continuity: Moving from Habitat II to Habitat III]

For the New Urban Agenda, the policy unit is urging

that this approach be taken further, suggesting that leaders in Quito agree to

inculcate a whole series of rights. These include rights to “habitat”, “public

space as a component of the urban commons”, “a safe and secure living

environment”, “participatory and inclusionary urban planning”, “mobility and

accessibility”, “safety, security, and well-being”, “environmental protection”,

and in order to “access the benefits of city life”, “access basic essential

services and infrastructure” and “socially produce the habitat and the city”.

‘Not appropriate forum’

In response to the paper on the right to the city,

some countries have applauded this approach based on their own legal

frameworks.

Ecuador, the HabitatIIIhost country,

commented that its own constitution has already enshrined the right to the

city. France likewise noted that the very phrase “right to the city” was coined

by French philosopher Henri Lefebvre in 1968, and argued that its own

conception of the right to the city emphasizes spatial strategies through urban

planning and empowering local authorities.

Given that Ecuador and France are the co-chairs of

the Habitat III Bureau,

the committee of U. N.members that are guiding the New

Urban Agenda through the drafting process, this endorsement gives the right to

the city exceptional weight.

[See: The drafters: Meet the two women leading the Habitat III Bureau]

Brazil also endorsed this vision of the New Urban

Agenda and even suggested adding “the right to adequate food.” Norway and

Finland, too, joined the rights bandwagon, while the European Union as a whole

was cautiously in favour, while requesting more precise definitions of this

litany of rights.

The chief detractor, meanwhile, was the United

States. The country’s extensive response refuted every one of the

proposed rights line by line, claiming that they are not recognized as such

under any international human rights instrument.

“The Agenda is not the appropriate forum to declare

or recognize any new rights asUNHabitat is not a human rights

body,” theU. S.response stated, proposing

“cities for all” as an alternate framework that would avoid rights-based

language. Colombia also joined this stance.

Washington has historically had a kingmaker/spoiler

role in Habitat negotiations, according to multiple close observers. That

history sets up a potential showdown over rights language in the New Urban

Agenda. Given that many NGOs are aggressively promoting this framework for

Habitat III, there will probably be considerable noise on this topic

inside and outside the negotiating rooms.

Not that the right to the city is the only such

potential flashpoint. Elsewhere, in response to the housing policy framework, Russia requested the removal of “LGBT”

from a list of protected groups. Using similar logic, the Russian response

urged the removal of reference to alternative sexualities because “as a

category [it] has not been universally recognized as a special needs group

living in precarious conditions”.

Not in my backyard

As the policy-unit experts painted a picture of

global urbanization, they described a scenario that didn’t always resonate with

the experience of individual countries.

A common phrase in Norway’s comments was “we do not

recognize the description.” In Norway, which has one of the lowest Gini

coefficients in the world, phrases like “the current pattern of urban

development based on competitive cities [… is] not able to create a sustainable

model of social inclusion and [is] rather [an] exclusion-generator” simply did

not ring true.

Brazil similarly bristled at certain generalized

characterizations of the current state of cities. The harsh accusations, found

especially in the aforementioned policy paper on the right to the city,

essentially prompted a reaction of “not in my backyard” — even if such

criticisms may hold true in other parts of the world.

Elsewhere, Ecuador questioned what was meant by

“shrinking cities”. As a developing economy whose urban populations are growing

fast, its cities are anything but shrinking, a situation that holds true across

much of the developing world.

But across the Pacific, that concern is paramount.

Japan explicitly noted, “The New Urban Agenda is required to meet the needs of

different circumstances around cities, namely developing cities, developed

cities and shrinking cities.”

The Japanese claim that there will be more

shrinking than rapidly growing cities in the near future — and also offer their

expertise on the matter. “Japan, as a country facing rapid depopulation and

aging, is ready to provide our knowledge and experiences on how to deal with

shrinking cities,” its response stated.

Small, sharp differences

Drawing from nearly every country’s comments yields

a potpourri of additional issues.

Myanmar expressed concern that national urban

policies — Habitat III is likely to call for every country to develop

and adopt such a law — are not well understood and hard to implement. The

country also expressed concern that the proposed housing

framework, one which does not rely on massive public-sector

production but rather the creation of an “enabling environment” for social

housing, “a major change for government ways of thinking.”

Senegal called for enhanced recognition of the

importance of urban agriculture. Norway lamented the lack of any mention of

public health and asked for more on climate change. Brazil warned that there is

no single ideal model for compact urban development, which is the gold standard

for the anti-sprawl sensibility among many key figures in the Habitat III process.

Argentina vigorously supported an increased role

for local authorities. That constitutes a reversal of the country’s position in

negotiations on Habitat III thus far — probably reflective of the new

presidential administration, with former Buenos Aires Mayor Mauricio Macri now

occupying the Pink House.

[See: U. N.General Assembly approves Habitat III rules,

ending 8 months of limbo]

Such small but sharp differences are a reminder of

the difficult task of crafting a universal agenda. It is an exercise that the

shepherds of the Sustainable

Development Goals (SDGs), theU. N.’s

new 15-year strategy to end extreme poverty, undertook all last year.

In 2012, the U. N.agreed

that the SDGs would apply to both developed and developing countries. The Millennium

Development Goals— which the SDGs replaced — only applied

to the developing world. Bridging the global socio-economic divide became the

central challenge of forging the SDGs.

In coming months, the drafters of the New Urban

Agenda will face a similar hurdle. In urbanization, no different than

development, the planet hardly looks the same from every angle.

Photo: Sworup Nhasiju