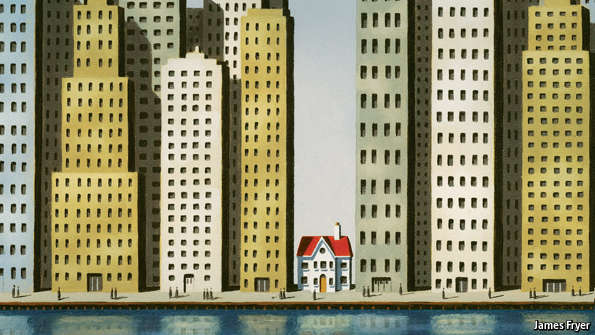

BUY

land, advised Mark Twain; they’re not making it any more. In fact, land is not

really scarce: the entire population of America could fit into Texas with more

than an acre for each household to enjoy. What drives prices skyward is a

collision between rampant demand and limited supply in the great metropolises

like London, Mumbai and New York. In the past ten years real prices in Hong

Kong have risen by 150%. Residential property in Mayfair, in central London,

can go for as much as £55,000 ($82,000) per square metre. A square mile of

Manhattan residential property costs $16.5 billion.

Even in these great cities the

scarcity is artificial. Regulatory limits on the height and density of

buildings constrain supply and inflate prices. A recent analysis by academics

at the London School of Economics estimates that land-use regulations in the

West End of London inflate the price of office space by about 800%; in Milan

and Paris the rules push up prices by around 300%. Most of the enormous value

captured by landowners exists because it is well-nigh impossible to build new

offices to compete those profits away.

The costs of this misfiring property

market are huge, mainly because of their effects on individuals. High housing

prices force workers towards cheaper but less productive places. According to

one study, employment in the Bay Area around San Francisco would be about five

times larger than it is but for tight limits on construction. Tot up these

costs in lost earnings and unrealised human potential, and the figures become

dizzying. Lifting all the barriers to urban growth in America could raise the

country’s GDP by between 6.5% and 13.5%, or by about $1 trillion-2 trillion. It

is difficult to think of many other policies that would yield anything like

that.

Metro

stops

Two long-run trends have led to this

fractured market. One is the revival of the city as the central cog in the

global economic machine (see article). In the 20th

century, tumbling transport costs weakened the gravitational pull of the city;

in the 21st, the digital revolution has restored it. Knowledge-intensive

industries such as technology and finance thrive on the clustering of workers

who share ideas and expertise. The economies and populations of metropolises

like London, New York and San Francisco have rebounded as a result.

What those cities have not regained

is their historical ability to stretch in order to accommodate all those who

want to come. There is a good reason for that: unconstrained urban growth in

the late 19th century fostered crime and disease. Hence the second trend, the

proliferation of green belts and rules on zoning. Over the course of the past

century land-use rules have piled up so plentifully that getting planning

permission is harder than hailing a cab on a wet afternoon. London has strict

rules preventing new structures blocking certain views of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Google’s plans to build housing on its Mountain View campus in Silicon Valley

are being resisted on the ground that residents might keep pets, which could

harm the local owl population. Nimbyish residents of low-density districts can

exploit planning rules on everything from light levels to parking spaces to

block plans for construction.

A

good thing, too, say many. The roads and rails criss-crossing big cities

already creak under the pressure of growing populations. Dampening property

prices hurts one of the few routes to wealth-accumulation still available to

the middle classes. A cautious approach to development is the surest way to

preserve public spaces and a city’s heritage: give economists their way, and

they would quickly pave over Central Park.

However well these arguments go down

in local planning meetings, they wilt on closer scrutiny. Home ownership is not

especially egalitarian. Many households are priced out of more vibrant places.

It is no coincidence that the home-ownership rate in the metropolitan area of

downtrodden Detroit, at 71%, is well above the 55% in booming San Francisco.

You do not need to build a forest of skyscrapers for a lot more people to make

their home in big cities. San Francisco could squeeze in twice as many and

remain half as dense as Manhattan.

Property

wrongs

Zoning codes were conceived as a way

to balance the social good of a growing, productive city and the private costs

that growth sometimes imposes. But land-use rules have evolved into something

more pernicious: a mechanism through which landowners are handed both

unwarranted windfalls and the means to prevent others from exercising control

over their property. Even small steps to restore a healthier balance between

private and public good would yield handsome returns. Policy makers should focus

on two things.

First, they should ensure that

city-planning decisions are made from the top down. When decisions are taken at

local level, land-use rules tend to be stricter. Individual districts receive

fewer of the benefits of a larger metropolitan population (jobs and taxes) than

their costs (blocked views and congested streets). Moving housing-supply

decisions to city level should mean that due weight is put on the benefits of

growth. Any restrictions on building won by one district should be offset by

increases elsewhere, so the city as a whole keeps to its development budget.

Second, governments should impose

higher taxes on the value of land. In most rich countries, land-value taxes

account for a small share of total revenues. Land taxes are efficient. They are

difficult to dodge; you cannot stuff land into a bank-vault in Luxembourg.

Whereas a high tax on property can discourage investment, a high tax on land

creates an incentive to develop unused sites. Land-value taxes can also help

cater for newcomers. New infrastructure raises the value of nearby land,

automatically feeding through into revenues—which helps to pay for the

improvements.

Neither better zoning nor land taxes

are easy to impose. There are logistical hurdles, such as assessing the value

of land with the property stripped out. The politics is harder still. But

politically tricky problems are ten-a-penny. Few offer the people who solve

them a trillion-dollar reward.